The world is making deliberate strides toward a renewable-energy future, which promises to limit damage to the climate from fossil fuel emissions. At the same time, the world is moving with breakneck speed toward a climate emergency.

The transition to renewable energy is not going nearly as well as it needs to, and also not nearly as well as many argue that it is going. We need to build the renewable energy future, and we are not building it fast enough.

I am a pro-renewables partisan, not an opponent, but I believe that overstating the progress and understating the challenges leads to complacency in those who don’t understand the real situation, as well as to decreased trust in the renewable-energy movement from those who do.

I’ll describe this landscape in five parts:

- The Friction-Free Future – Why you might be optimistic about the Energy Transition

- How is the Energy Transition Going? You have to look at the numbers, and look at the right numbers. When you do that, you find that the progress is much too slow.

- The Frictional Present – Why is the transition so hard?

- Unhelpful Advocacy – Renewables advocates often present a distorted picture, and advocate for the wrong things

- The Ground Game – What we need to focus on as communities, advocates, and voters

The Friction-Free Future

Renewables advocates have long pointed to the astonishing declines of the core costs of wind and solar energy, with a message of hope for the future.

As part of a dual strategy of 1) make electricity green and 2) electrify everything, low-cost renewable energy has the promise of cutting carbon emissions out of vast swaths of the economy. It’s true that not everything can be electrified, and significant contributions to atmospheric carbon will remain even after the electric grid is decarbonized and we plug as much as we can into that grid (think: cows). But a thorough transition to low-cost renewable energy could seemingly get us much of the way toward stabilizing atmospheric carbon levels and staving off the most catastrophic climate scenarios. “Low cost” is the key.

For as long as the core unit costs of renewable power remained higher than the cost of fossil fuels (all-in, including subsidies), rational economic actors will ignore renewable alternatives, unless compelled by government action. The moment that the cost of renewable power becomes genuinely cheaper than the cost of fossil power (so the argument goes), we should expect a phase transition, and renewable power will quickly take over the world.

Imagine a vast continental plain of power plants managed by rational economic actors, where coal-fired power plants produce energy at a cost of $35 per megawatt-hour (MWh). When the most cost-effective solar or wind installation achieves $36 per MWh, nothing changes. The moment that the solar or wind cost reaches $34 per MWh, though, renewable technology goes from zero demand to nearly infinite demand. Renewable power spreads out through the landscape, instantly, like a superconducting superfluid – because that’s how rational actors and ideal markets work.

Of course even the most passionate and visionary advocates of renewable power never thought it would be quite that simple. But the core idea is that differential cost creates a tipping point, and on the other side of that point we should expect the transition to move very quickly.

How is the energy transition going?

That’s the vision – how is the progress in reality? Two things are true simultaneously:

- Renewable-energy technology has been making mind-blowingly fast progress (in some specific senses and locations and sectors), and

- The overall energy transition is far too slow to make the necessary impact on mitigating climate change.

How fast does the transition need to be going? For this piece I assume the U.N.’s target of net zero global emissions by 2050, which was originally conceived to keep global temperatures within an additional 1.5° C above pre-industrial levels. Projections of a world with substantially warmer temperatures than +1.5° C are grim.

The pace of renewable energy technology

If you look at renewable energy in isolation, it is easy to find reason for optimism. Enormous effort and capital is being put into new wind and solar installations, in response to both direct profit motives and subsidies. The world added 50% more renewables capacity in 2023 than it did in 2022. The cost of base solar modules continues to decline, huge wind farms are everywhere you look if you drive through the center of the U.S., and new records for installation and renewable energy production are set daily.

The energy landscape is complicated, though, and there are many metrics and numbers, and ways to slice and dice them. It is always possible to select your metrics and numbers to look half-full or three-quarters full, or three-quarters empty, which makes the debates between optimists and pessimists confusing and tiring.

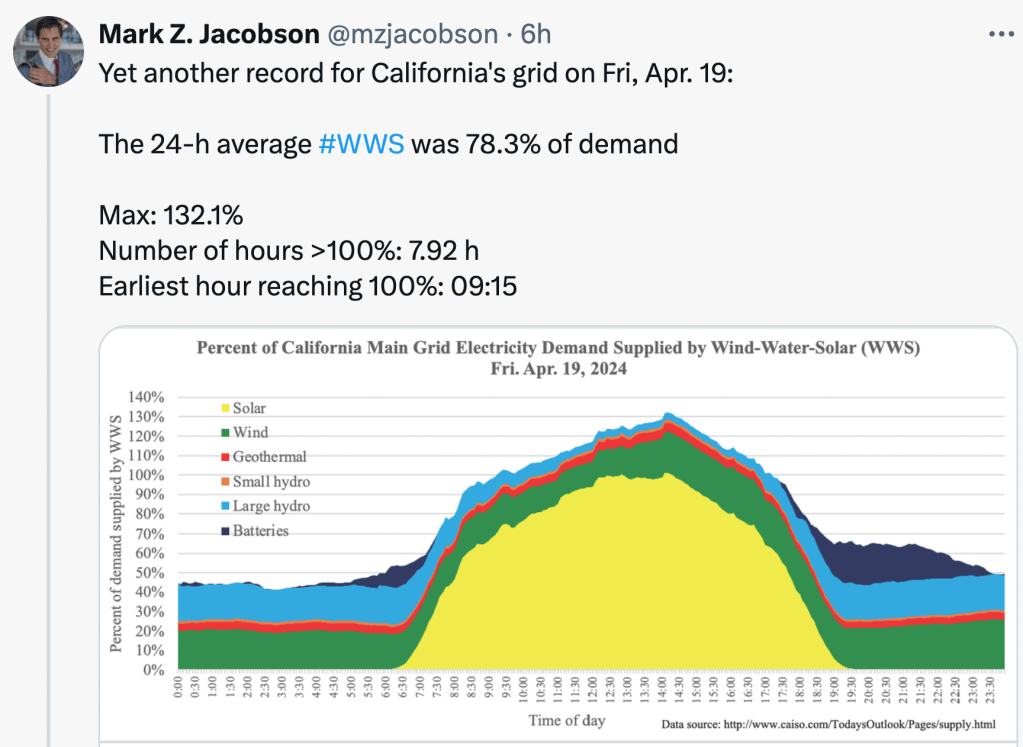

There is a particular flavor of renewables triumphalism that I would like to call out, exemplified by the following tweet:

Nothing against this particular commentator, as Jacobson is an academic expert in atmospheric sciences, a close and astute observer of the renewables scene, and a dedicated advocate for a clean-energy future. The tweet is a single example, fairly randomly chosen, standing in for a widespread genre of optimistic cheerleading about recent achievements in renewable energy.

Whether this is a good genre to have around depends both on the communicative intent and how it’s likely to be read. Is the intent to celebrate a recent success, and inspire us by pointing at a possible future? That may be fine if so. Is it intended as a representative summary of how the energy transition is going? I’m hoping not. Could a casual reader look at this tweet and think “Wow, 78.3% renewables! This renewable-energy thing is like almost 80% done!” Quite possibly, and if so, so much the worse for the tweet, as the casual reader would then have been deeply misled.

Note first that this is a set of statistics about one particular day (2024-04-19) and one particular locale (California). Also note the oddity of the quoted statistic: the average of hourly renewables as a percentage of overall demand over the course of that day is 78%. This is a bit like the statistically-trained archer who misses the target to the left, then misses to the right, then declares that their average shot is a bullseye. An average in this case is the perfect measure to impress with magnitude, while skipping over one of the core challenges of renewable energy – that it is intermittent, meaning that some of the time you get less than you want and some of the time you get more than you want, and that this is a problem, not a virtue.

So let’s not look at particular days, places, or metrics that have been carefully chosen to look as good as possible. Instead let’s look at aggregate numbers over longer periods of time.

The transition by the numbers

For simplicity and comparability, in this section I restrict myself just to the last 10 calendar years for which we have good numbers (sometimes 2014-2023 and sometimes 2013-2022).

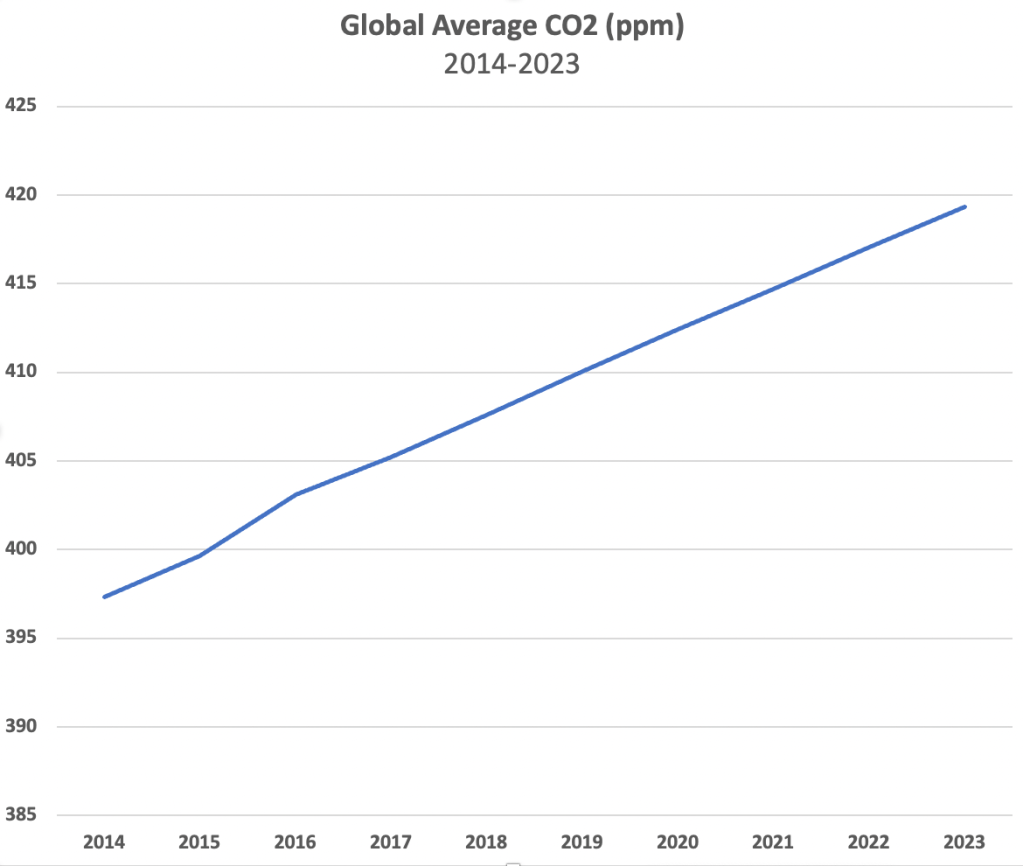

Atmospheric carbon – the core thing we care about

Here’s average atmospheric CO2, globally, over the last ten years. This is the scary inconvenient truth about our current trajectory, and we look to the energy transition to bend this curve downwards.

Source: Lan, X., Tans, P. and K.W. Thoning: Trends in globally-averaged CO2 determined from NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory measurements. Version 2024-04 https://doi.org/10.15138/9N0H-ZH07

The obvious thing to point out is that the slope of this curve is remarkably constant. If the energy transition will ultimately put a knee in that curve to make it stop rising, or even just to slow its growth, we haven’t seen it yet.

For the rest of this section I stay within the past decade, but focus on the energy transition in the United States. This is not because other geographical areas don’t matter, or other timescales aren’t illuminating to look at, but to make apples-to-apples comparisons with well-sourced data. Many of the same issues and trends that we see in the U.S. also apply more globally.

Greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S.

Here’s the last decade of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S, by million metric tonnes of CO2- equivalent warming power:

Source: US EPA. https://cfpub.epa.gov/ghgdata/inventoryexplorer/index.html#allsectors/allsectors/allgas/gas/all

This looks just slightly better than flat. Overall CO2-equivalent emissions declined 7.3% from 2013 to 2022. Before we declare a renewables victory, much of this decline is due to substituting somewhat-cleaner fossil natural gas for coal. Some of the rest has resulted from moving some industries offshore.

A graph of flat emissions over time roughly corresponds to a steadily rising slope of carbon concentration over time, as we saw in the beginning.

What creates these emissions?

Data source: U.S. EPA. https://cfpub.epa.gov/ghgdata/inventoryexplorer/index.html#allsectors/allsectors/allgas/econsect/all

The three sectors with the largest contributions are transportation, industry, and the electric power grid, which is responsible for up about 25% of U.S. GHG emissions as of 2022.

Of these, the electric grid is usually thought of as the easiest to decarbonize, as large-scale utilities should straightforwardly be able to deploy wind and solar installations at large scale. Transportation is being decarbonized in part by battery-powered electric vehicles, but that power has to ultimately come from the electric grid. Industrial uses (like steel and cement) are the most challenging to electrify and make green.

Renewable vs. fossil energy

When we talk about the energy transition, we implicitly imagine increased energy contribution from renewables, with resulting decreased use of fossil fuels. So what does that look like for the current electric grid (the easiest case)? (For this section and the rest of the piece I lump all energy production into three categories: fossil, renewable, and nuclear. Fossil includes coal, oil, and natural gas; renewable energy includes wind, solar, geothermal, and hydropower; nuclear is in a category of its own, even though it is not a carbon-emitting fuel)

Data source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Monthly Energy Review, October 2023, Table 7.2a Electricity Net Generation Total (All Sectors) and Table 10.6 Solar Electricity Net Generation. Zero-carbon generation does not include generation from distributed or small-scale solar PV.

If you squint hard, you see apparent progress in the “green” part of the graph, taking the percentage of the grid demand supplied by renewables from 12.3% to 21.4%, and decreasing the fossil contribution from 67.3% to 59.5% (part of which is due to replacement of fossil coal with fossil natural gas). That progress took a decade to accomplish.

Renewables have gained as a percentage of total contribution, and fossil generation has declined as a percentage, but the picture is slightly less attractive in absolute terms, as overall production has risen.

In 2022, total renewables production was 75% higher than in 2013, which nets out to 6.4% annualized growth. Total electricity production went up by 4.4% during the same period. With total nuclear generation essentially unchanged, a little less than half of the absolute production gain from renewables was “spent” on increased overall production, leaving a little more than half of it to be spent reducing fossil production. The upshot for fossil electricity production was a total decrease of about 7.2%, which annualizes to about –0.82% per year.

Future projections

All the numbers and charts and graphs above are about the past, which is easy to agree about. One reason to focus on the U.S. for apples-to-apples comparisons is that organizations like the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) keep very good statistics on energy production and emissions growth.

Agreement tends to disappear when talking about the future. In particular, how do we extrapolate the future trajectory of renewable energy growth? Optimists look at the above graphs and see the small inroads of renewables into overall energy production as the beginning of an exponential curve, and expect an accelerating rate of adoption. (It should be said that the speed of solar module cost declines over the last few decades consistently outperformed the most optimistic projections.) Pessimists and moderates are more likely to extrapolate linearly, or see a sigmoid curve – growth that looks exponential at the start, and then runs into limiting factors and diminishing returns, and plateaus.

Imagine that our goal is not net-zero for the electric grid, but the more modest goal of decreasing fossil contribution by 90%, down to 10% of 2024 levels. At the rate of fossil electricity reduction we saw in 2013-2022 above (-0.82% per year) we would reach this goal … 280 years from now, in the year 2304.

Of course, this is a pessimistic and bogusly linear extrapolation – in much the same way that you make faster progress in paying off a fixed-rate mortgage as you go, it’s reasonable to expect renewable electricity to grow in an exponential manner, at least for a while, and for corresponding declines in fossil contribution to accelerate (much like paying off the principal).

A better-faith set of assumptions would be to project out the annualized (exponential) growth rates for renewables and for total production. Let’s assume that that growth rates per year are as follows, extrapolated from the 2013-2022 data above:

- Renewables: +6.4%

- Nuclear 0.0% (stays flat)

- Total production: +0.47%

- Fossil production: ??

Assume that fossil production picks up the slack, so fossil production = total production – (nuclear + renewables). Projecting this forward from 2022 levels, we get a graph that looks like this:

Under these assumptions, the U.S. electricity grid reaches net zero carbon emissions sometime in early 2046. Not bad, right?

Not so fast

Before we see this as being in line with net zero by 2050, note that this is decarbonization of the electric grid only, which is currently only 25% of the emissions problem in the U.S. By this projection we could use up all the projected growth in renewable energy in this time period on that alone, without touching the other 75%.

Secondly, this assumes a rate of electricity growth (+0.47%) based on the last 10 years in the U.S. – a rate that was negligible and probably anomalously low. There seems to be broad agreement that overall energy demand will continue to accelerate both in the U.S. and worldwide. As developing economies continue to develop, their per capita energy utilization is likely to become more similar to that of the First World. And new uses for energy keep arising – most recently the huge uptick in demand for electricity from data centers and AI.

The decarbonization picture is a race between renewables growth and demand growth. We succeed only to the extent that renewables growth greatly outpaces demand. For example, in a world with 3% demand growth and 3% renewables growth, when do we reach Net Zero? Never.

The EIA’s own projection is that global electricity generation will grow by between 30% and 76% by 2050, and that that will actually outpace renewable-energy growth, with the result that net emissions rates will be higher in 2050 than they are now. If they turn out to be right, this is not the “transition” that we’ve been hoping for.

Summary

The energy transition to date is moving, but appears to be moving too slowly to halt carbon emissions in the U.S. within a span of two or three decades. Creating significant declines in emissions growth will require decarbonizing not only the existing electric grid and its rising demand, but equally large sectors like transportation and industrial uses, whether that is via electrification (and corresponding increased demand on the grid) or by other means. The existing electric grid is the easy part, and as easy parts go, it seems to be remarkably hard, and slow to decarbonize.

The Frictional Present

Why is the transition so hard, and why is it moving so slowly? What kinds of sand are in the gears of the energy-transition machine?

The obvious complexities – intermittency and transmission

Conventional energy technologies (both fossil and nuclear) can produce a steady and predictable stream of energy, and in the case of fossil power there is wide latitude about where to site the production.

Both wind and solar power are intrinsically intermittent – they only work when the sun is shining and/or the wind is blowing.

Also, the best places to produce wind and solar tend to be far away from the greatest energy demand. Solar is best produced in very sunny places where land is cheap – in the U.S. this turns out to be predominantly the middle and southwest of the country. Wind is best produced where it is the windiest, and where land is cheap, and in rural areas where fewer people will be bothered by the distraction of huge turbines with blades spinning on top. In practice, we don’t put wind turbines in the middle of large coastal cities (although maybe we should start?), which means that the largest potential consumers of renewable energy don’t live anywhere near where it will be produced.

So wind and solar present challenges in both time and space. If you could capture solar energy in Texas, put it in bottles, and then instantly teleport the bottles for free to Manhattan and Malibu to be used whenever needed, the transition would be very different and much easier. But battery and storage technologies are not currently up to this task, and transmission lines are expensive and capital-intensive.

Storage

Although other durations present even greater challenges, the poster-child use case for battery storage is the daily cycle: solar cells can only harvest energy during the day. Production is highest when the sun is highest, and demand has bimodal peaks in early morning (7am – 10am) and late afternoon/evening (4pm – 9pm), driven especially by air conditioning.

The solution seems simple: store energy in batteries when the sun is high, and get it back from the batteries in the evening and morning. There’s just one problem: batteries are expensive, and also just … not very good. As the saying goes “There’s no Moore’s Law for batteries“. Utility-scale batteries made with the dominant chemistry (lithium-ion) have round-trip efficiencies of 80% to 85% (meaning you lose at least 15% of the power you put in), can typically be used for a maximum of four hours of discharge at full capacity, and are about as costly to store renewable energy in as it costs to make the energy in the first place.

So if your solar installation costs you, say, $0.04 per kilowatt-hour when you’re running it at noon, and you use some of those kWh’s immediately and store the rest to use at 8pm, the immediate-use kWh’s will cost you $0.04 each, and the stored-and-retrieved kWh’s will cost you $0.08 each ($0.04 for production and $0.04 for storage). The fact that the sun goes down turns out to be really expensive.

On top of cost and capacity challenges, lithium-ion batteries need lithium, which is scarce and presents supply-chain challenges – and also lithium-ion batteries tend to catch fire. What’s not to like? Alternative chemistries like iron-flow and iron-air batteries have promise for longer durations but are just beginning to be proven and rolled out at scale.

Transmission

In general, if you want to get electricity from Point A to Point B, you need to physically connect A to B with wires. (This is as opposed to energy stocks like hydrogen or gasoline which need to be transported in canisters on ships, trains, or trucks). If your wind farm is in western Wyoming and your YouTube-watching electricity consumer is in West Hollywood, there needs to be an unbroken and reliable chain of transmission lines between those points.

Because prime renewables-production locations tend to be much further away from end users than is true for fossil fuels, renewable power needs to be transmitted over longer distances.

Building transmission is expensive, and normal transmission lines lose a lot of power. Typical losses are 2% to 4% per hundred miles. If you average that at 3% loss per 100 mi., then about 1/4 of the green power you produce in Wyoming for use in Hollywood will be lost along the way. Although electrons aren’t actually sent off with a destination address label, but participate in a super-complicated set of load-balanced grids, the fact that renewable energy is often consumed far away from where it is produced wastes a lot of energy.

If you assume a recent Biden administration target of 100% renewable electric power by 2035, it’s been estimated that the U.S. would need to expand its total transmission capacity by a factor of between 1.3 and 2.9 times current levels, both to accommodate longer transmission distances and to accommodate increased total load.

How much the challenges of intermittency and location matter depends heavily on how much reliance we are putting on renewable technology as the main energy solution. If wind or solar is a nice-to-have, or an add-on at those moments when it is actually cheaper than the alternative, then it may be OK if it is intermittently available. In a future where all energy is renewable, then combined renewable-energy solutions will somehow have to be reliable and always-on.

Capital

Just like a when a homeowner contemplates putting solar panels on the roof, there is a disconnect in renewable energy between investment time and payoff time. The wind or solar installations might in some cases have a useful lifetime of 25 years, but they have to be built now, and paid for now.

This means that profitability for renewable-energy projects is extremely sensitive to the cost of capital (i.e. interest rates). The last decade or so has been an anomalously great time to do renewables development, as the cost of capital was very close to zero. That time appears to be over. Increases in interest rates in the U.S. are causing cancellation of long-planned wind and solar projects that promised to be net profitable, but no longer will be profitable given higher rates. High rates equal a slower transition.

Capital needs are not just about renewable energy production itself. The technological solutions for location and intermittency (i.e. new transmission lines and long-duration battery storage) require new capital of the same order of magnitude.

A return from an era of free money to a more typical interest rate environment just highlights the fact that the full energy transition as we envision it will require an enormous amount of capital. (One estimate puts the total cost of full global decarbonization at $215 trillion.) Can a combination of the world’s businesses and the world’s governments summon up the capital investment that the transition will need?

NIMBY (the view from 30,000 feet)

If you fly from New York to San Francisco (as I’m sure we all do, frequently) and you look out the window on flyover country, you might find yourself saying “Look at all that land! Plenty of room for solar and wind! Good thing no one lives there!”

Actually, people do live there, they are just too small to see from that altitude. But if you want to find some of them, just jump out with your parachute, and wherever you land put up a sign that says “Wind farm permit meeting – call for comment”, and you will begin to meet some folks.

People support renewable energy development when it is far away from them

There is broad support in the U.S. for renewable-energy development, in theory – in a June 2023 poll, 67% of those polled thought that the U.S. should prioritize renewable energy technology.

But most people really don’t want a renewables installation to be very close to them. One survey found that people living within three miles of a 100MW-or-larger solar project had negative attitudes outweighing positive attitudes by a ratio of 12 to 1. Wind farms draw even more negative sentiment, being much taller and visually distracting (see anti-wind-farm stickers here). And despite how the land may look from an airliner in the middle of a flyover, there is almost no potential renewables site anywhere in the U.S. that isn’t close to someone.

Anecdote: A county hearing

An eye-opening experience for me was sitting in on a county supervisors hearing in a very rural corner of a Southwestern state. The proposed wind farm was to be entirely located on land of a large private landowner, with at least a mile between the border of the private land and the nearest turbine. Visual simulations showed that the wind farm as viewed from the nearest point not owned by the landowner was just barely detectable on the horizon.

It’s hard to think of a renewables siting situation that should be less vulnerable to NIMBY complaints. Yet the opposition testimony from nearby residents was passionate, angry, vituperative, and times crazy-seeming. Objections included noise, visual distraction, impact on birds, increased traffic from building and servicing the farm, as well as much more speculative theories about the health impacts of wind turbines located multiple miles away. Some of the residents were particularly angry because they didn’t feel they had received sufficient notification of the hearing; this turned out to be partly due to them being part of a back-to-the-land anti-government movement where people buy land and then build on it without registering their dwelling in any way with the county. The developer had relied on county records of addresses where people lived, and as a result had no idea that the angry constituents were there, needing to be notified. But announce a wind-farm hearing and you will learn that people live nearby.

Renewables development: winners and losers

Whatever the reasons are for the negative reactions are, people don’t like living near renewables farms. Wind and solar deals can be lucrative windfalls for landowners large and small, which means that a farmer with renewables leases may be very happy, and all of his immediate neighbors very unhappy. Unhappy with the visuals, and unhappy with the noise, distraction and extra traffic. Even if there are some trickle-down effects from renewables developments to county tax bases, immediate neighbors may still feel that they are net losers.

Looming soon, as more and more wind and solar farms are built out in non-coastal states, is the potential for analogous strife between the energy-producing and energy-consuming states. How long will residents of Texas, Nebraska, and Arizona be happy putting up with ubiquitous wind farms churning out power for the benefit of the residents of Los Angeles?

NIMBY matters for transmission too

It isn’t just the static wind and solar farms that are blocked and slowed by local opposition and NIMBY. Large-scale long-distance power transmission is crucial if low-cost renewable energy is to travel between where it is best produced and where it is most needed. These projects need rights of way, and involve a lot of disruptive construction. A similar pattern unfolds with top-down corporate investment and federal and state support running into local opposition, and municipal and county officials that stand with that opposition.

Bureaucracy and permitting

Developers who want to create a new wind or solar farm need to secure multiple different kinds of permits before the project is green-lit, and permitting itself is usually a slow, multiple-year process. Types of permits include land use permits, construction permits, and environmental permits (the last of which we’ll have much more to say about below). These permitting requirements were in the main well-meant when they were drafted, and are designed to prevent various kinds of real abuses. In combination, though, they form a layer of molasses in which renewables projects can be stuck for years. It is not enough that we can collectively eventually build out a renewable-energy-powered world – it needs to be built with urgency and quickly.

Similarly, interconnection queues (lists of requests to have renewables plants connected to the electric grid) move achingly slowly. In 2022, interconnection requests that were granted had been waiting an average of five years. This is partly an issue of transmission capacity needing to be built, and partly just that bureaucratic wheels grind slowly.

Business friction and business climate

We already covered the sheer cost of capital required to develop renewable energy projects. Other factors contribute to making the renewables-development business complicated, uncertain, and potentially unprofitable.

Bespoke deals

Developers who want to build a wind or solar plant typically need to find a plausible site, work out options deals with landowners for the land to build it on, apply for interconnection with the grid owner, set all the permitting steps listed above in motion, and finally strike a deal with someone who is going to buy their power. These are often Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) with electric utilities, which set out the prices and very complicated terms under which the developer will get paid for supplying electricity to the grid. Often the PPAs are landed in response to a Request For Proposals (RFP) where the utility has a formal (and often slow) process to get competitive bids from suppliers. Then once all that is in place, and a PPA is secured, the work of hiring, constructing, and operating the renewables farm can begin.

Then, for the next deal, the developer … does it all again. All of the deals that were negotiated for the first installation have to be negotiated anew for the second. By and large there is no cookie-cutter process yet where a developer can copy out the standard permitting responses, standard landowner offer, and the standard PPA terms and do this project just like the last one.

The cost of deals that don’t complete

With many years of process and delay in between conceiving the idea of a renewable-energy plant and the day that it starts pumping out green electrons, many proposed projects end up dying on the vine. Either they get definitively killed by permitting problems and local opposition, or they are in development for long enough that some fundamental assumption that made them make economic sense is no longer true (demand, cost of capital, competitive projects). The winning projects eventually have to pay for the losers.

Labor supply

Renewables farms typically have low labor costs in the operational steady-state, but require a lot of construction labor to actually create the installation. The U.S. in 2024 happens to be in a tight labor market, which means that certain kinds of labor are either more expensive than projected, or are simply unavailable. This can kill projects, but more often (a general theme here) the project will complete, but more slowly.

Supply chains

Solar installations, wind turbines, and electric cars are all very complicated machines, with parts and raw materials sourced from everywhere in a globalized economy. Large components include solar cells, wind turbine blades, and EV batteries. Raw materials range in ubiquity from iron and steel on one hand to rare earth metals like neodymium and praseodymium that are used to make the magnets for wind turbines and the motors in electric cars.

Since large renewables projects need to be planned years in advance, developers need to watch not only the current state of supply for their parts and materials, but have to try to project forward what those supply chains will look like in the late stages of a project.

Trade and tariffs

Many kinds of world events can disrupt the necessary supply chains, from wars to political instability to natural disasters. Trade wars and tariffs are especially determinative of the cost and availability of parts and materials and, although avoidable in principle, may change radically with the political winds and with changes of political administrations.

The dominant example here for the U.S. energy transition is the U.S/China relationship with regard to solar panels, lithium batteries, and key minerals needed for the transition. China can make many of these components at scale and more cheaply than any other country can, while engaging in trade practices that make their neighbors cry foul. U.S. political discourse around bringing back domestic manufacturing leads to “Made in America” pitches around renewable energy, and makes protectionist tariffs more attractive. This despite the fact that the domestic versions of these industries are not yet cost-competitive with China, and tariffs make overall cost of a renewables project more expensive. Projects that are on the border of projected profitability are likely to be canceled when a new tariff is announced.

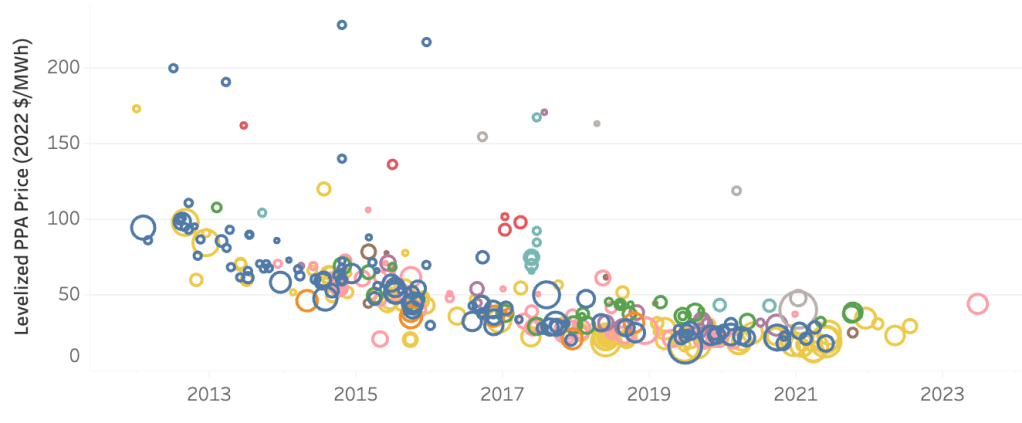

Non-module costs grow in significance

We started this piece with a graph of plummeting solar panel prices, showing the promise of cost-competitive solar. When solar modules were the dominant cost in making a solar farm work, this was a reasonable thing to focus on – and solar-panel costs have indeed had an astonishing Moore’s-Law-style exponential improvement consistently over the past few decades.

The real cost of a renewables plant, however, is the sum of all the costs that go into it. We might caricature the cost of a solar plant as something like: Total cost = cost(panels) + cost(construction) + cost(transmission) + cost(land) + cost(permitting) + cost(management) + …

Some of these costs, like costs of the panels themselves, have Moore’s Law dynamics where they become exponentially cheaper over time. Others are stubbornly grounded in human or physical realities that limit how fast they can become cheaper. Some resources that have a fixed total amount (like land) will inevitably become more expensive over time as that total amount is progressively claimed.

The overall principle is: the cheaper a cost component becomes, the less its cost matters in the overall cost. The cheaper solar panels are, the less we care how much cheaper they continue to get versus other costs.

This helps to explain why, although solar panels have continued to decline in cost over the last ten years (same data as our first chart, with recent years only and a linear plot rather than logarithmic),

the best measure of all-in utility-solar cost – the Power Purchase Agreement, or PPA, which represents the price that solar developers charge the utilities per megawatt-hour – has declined much more slowly, has been largely flat for the last five years, and may have even ticked upward in 2023.

Source: https://emp.lbl.gov/pv-ppa-prices. Colors correspond to different U.S. utility regions.

Prime renewables sites are scarcer than they seem at first

Imagine that you are the first developer ever to site a large solar farm in the U.S., and you are looking for the best square mile for the project that you can find. You would care about a lot of factors, in no particular order:

- Insolation (how sunny is that square mile?)

- Topography (land should be either flat or slightly south-facing)

- Proximity to grid interconnection

- Proximity to highway or rail for equipment transport

- Grid demand from local utilities

- Land cost in the area

- Willingness of land owners to lease

- Receptivity of county/city authorities

- Ease of permitting

- Receptivity of community (NIMBY issues?)

In the case of wind projects, the first couple of considerations would be be completely different (wind speed rather than insolation etc), but most of the later factors would be similar.

You could imagine a scorecard that weights all of these factors to come up with a single desirability score for a given square mile. Imagine further that you can evaluate every possible square mile in the U.S. against your scorecard, and you settle on the one with the best score. (Real-world examples of such scorecards include the Kontur platform and Landgate’s LandEstimate),

As you move on to your second project, one thing is obvious: your second site won’t have a better scorecard score than your first – otherwise you would have chosen the second one instead. If we are choosing our square-mile sites perfectly with perfectly fine discrimination, then every site we choose be worse than the last.

Although we’ve set this up to be definitionally obvious, how much does it matter? Don’t we have huge amounts of available renewables sites in the U.S. that are essentially equivalent? If we graphed the scorecard scores of each new site over time, wouldn’t it still look like a nearly flat line?

How much land are we talking about?

A rough guess at how much U.S. land is occupied by utility-scale solar farms right now is 820 square miles. (That is based on 61.7 GW installed capacity (as of 2022) times an estimated 8.5 acres per MW or 0.0133 sq. mi. per MW.) If we have doled out our square-mile solar sites in scorecard order, we are about to look at the 821st most-favorable site.

The U.S. has a total land area of 3,532,316 square miles, so our 820 square miles of solar farms to date is only 0.023% of the land available. It seems that we have plenty of land to play with.

Wind energy is different from solar energy in its land use. A solar farm is dense, and land currently used for solar can’t be used for anything else. Turbines in a wind farm are sparse, and the land in between them can potentially be used for other things such as agriculture, grazing, or even solar farms. The one thing that you cannot put in between a wind farm’s turbines is another wind farm, or more turbines. The “total land use” of a wind farm is the entire area it is spread over, which is locked up from the point of view of further wind development.

In the case of onshore wind farms, we have about 148 GW of installed capacity that (based on a rough estimate of 10 MW per square mile) occupies a total of roughly 14,800 square miles in total land use. This is about 0.42% of total land in the U.S., so again it seems that land should not be a serious constraint.

Some land is a lot better than other land

Here’s a map of how pure solar quality varies across the United States.

Source: https://www.nrel.gov/gis/solar-resource-maps.html

The very best solar-quality land (>5.75 kWh per square-meter per day) is located in a fairly narrow band in the Southwest (portions of California, Arizona, New Mexico and west Texas). By eye, this area is about 2/3 the size of total land in Arizona and New Mexico combined, for an estimate of about 155,000 square miles, or about 4.4% of total land in the U.S.

If we were the very first solar developer in the U.S., we would presumably choose our first square mile from this area, and then apply other filters, such as land cost, topography, grid proximity, and community receptivity (from landowners, permitting bodies, and NIMBY). If we assume that we have four such factors, that they are independent of each other, and that we insist on the top 20% for each of the factors, then we have 155,000 * (0.2)^4 = 248 square miles of absolutely prime solar land available, with no compromises made. If this were true, it would imply that we ran out of such prime land with our 249th square mile choice, and that choices 249 through 820 have suffered at least slightly but increasingly from compromises and tradeoffs. Obviously this estimate is crude and highly sensitive to both the independence assumption and the particular thresholds chosen. As an order-of-magnitude check, though, it indicates that the quality of currently-available solar land may already have declined because the very best sites have all been taken.

Here’s a corresponding map for wind energy:

Source: https://www.nrel.gov/gis/wind-resource-maps.html

This shows wind speed at 80 meters above ground, which is a typical height at which wind turbines operate.

If we ignore the offshore areas, it’s easy to see that land with the very highest category of wind speed (> 10 meters/second) is a tiny proportion of total U.S. land. Furthermore, these differences matter more in the case of wind speed than they did for solar insolation, because wind power generation varies as the cube (third power) of the wind speed. According to the map, wind speeds of 7.0 meters/second are available in large swaths of the Plains states. But accepting a speed of 7.0 m/s rather than 10.0 m/s means realizing only 34% of the power generation that 10 m/s would give you.

We argued above that the decline in quality of the best-available solar sites as the best spots are taken may be material even now. The same argument can be made with little change for wind, with the exception that the cube law for wind power means that wind-speed attractiveness probably declines more quickly than insolation attractiveness does in the case of solar.

Greater renewables penetration makes the hard problems harder

Renewable energy is a wonderful thing, especially when you don’t have to rely on it. If renewable sources provide 5% of the energy of your local electric grid, and only do that at times that are particularly profitable, then it makes for a nice-to-have supplement in the energy mix. But electricity-grid customers have very strict uptime requirements – when they flick a light switch, they expect the light to go on, and even an outage percentage of 0.1% (or one 8-hour period in a year) can make the customers quite irate.

The larger the percentage of the energy budget that renewables supply, the harder many of the above challenges and sources of friction get – especially the core challenge of intermittency.

Storage time scales

The most obvious solution to the intermittency problem is battery storage. Storage solutions can be deployed to account for variations of both energy demand and renewables supply. There are several time scales that matter:

- Short term. Batteries play a role here in regulating and smoothing out the flow of power.

- Day/night. Demand in the U.S. is typically highest from 7am to 10am and 4pm to 9pm, and solar supply is highest when the sun is highest, and nonexistent at night – this mismatch results in the the duck curve. Wind power compensates to some extent (with nights being windier than days). Dealing with this daily rhythm is right at the edge of what battery storage can currently do, in that storage durations that are measured in hours (which can cover the high-demand afternoon and evening) cost about as much in battery storage as the stored power costs to generate.

- Weekly rhythm. Demand is less during the weekend, so much longer duration batteries could be used to shift supply from weekends to weekdays, if it they were affordable.

- Seasonal. The sun shines much less brightly in the winter than in the summer. It would be nice to be able to store power in the summer and use it in the winter.

The seasonal timescale is the real killer here, due to both technical and economic considerations on batteries, and will be the last piece to be solved. Batteries pay for themselves through charge/discharge cycles, and so you can calculate how expensive a battery is by dividing its total cost by the number of those cycles in the lifetime of the battery. A battery system designed to battle the duck curve of day/night cycles might have hundreds of such cycles in a year. A purely seasonal battery could conceivably have just one charge and one discharge over the span of a year. It is very hard to see how such batteries would pay for themselves by their usage, and batteries might have to become a couple of orders of magnitude cheaper or more efficient before we can wean ourselves off the need for fossil power in the winter.

Curtailment

The solution other than storage is just to over-generate. Build out solar and wind generation so that even in at the worst times (dark of night in the middle of winter) there is enough power to meet demand. At those times that supply exceeds demand (noontime in summer) just throw away or curtail the excess power.

If renewable power were genuinely free, then this might be a reasonable approach, but the more power is curtailed, the less economic renewable power looks in comparison to traditional fossil sources. Curtailment episodes are sometimes necessary, but are seen as failure modes by the utilities. Curtailment problems and challenges will naturally increase as renewables sources take on more and more of the load.

The transition is a moving target

It is not enough that we see growth in the production of renewable energy. To even begin making a “transition”, renewable-energy production has to grow fast enough to cover increases in energy demand, and on top of that, actually shrink the contribution of fossil energy to the energy budget quickly enough that we can get to net zero in decades rather than centuries. The growth rate matters enormously, and currently the growth rate is too slow.

Summary

The dual challenges of intermittency and transmission make the renewable energy transition an intensely complicated endeavor. It requires deployment of completely novel technologies at continental scale to completely change how we produce and consume energy, without ever interrupting the energy flow that we depend on. And unfortunately that very large task needs to be accomplished under a deadline that, while it may have been of our own making, was definitely not of our choosing. Penalties of arriving at our destination a decade or two late seem likely to be severe.

A host of different challenges at all levels of the technical and societal stack seem to conspire to make it difficult to make the transition as quickly as we need to. Sources of friction include: interest rates and the cost of capital, hostility to renewables installations themselves (NIMBY), slow and arcane permitting processes, tight labor markets, supply-chain disruptions, tariffs and trade relations, one-by-one deal structures, the possible plateauing of overall cost reductions, and the very large but still finite set of ideal locations for renewables sites. Most of these sources of friction get more pronounced the larger the renewables share of the pie becomes, and yet our aspiration is for renewable energy to become the entire pie.

Lest this all sound too negative – despite all of these challenges, the U.S. has managed to grow its renewable-electricity contributions by a brisk clip of about 6.4% annualized over a decade, which is an amazing achievement. Public awareness of climate change as a problem has grown steadily as the actual climate situation has worsened, which may translate into more willingness to take action. My final section – on what we can do as communities, advocates, and voters – will be more positive, I promise. First, though, we need to talk about how we talk about renewable energy.

Unhelpful advocacy

The overall energy transition picture is immensely complex, and correspondingly difficult to project into the future. For advocates who believe in the importance of this transition, the first persuasive hurdles are just in expanding the consensus that global climate change is real, that it results from human activity that emits greenhouse gases, that continued emission of greenhouses gases will continue to make the problem worse, and that greenhouse-gas concentrations that are much higher than in the present-day will lead to some very bad outcomes. (I have assumed that anyone reading this believes all of this already, and haven’t even spent any ink talking about how to advocate for this level of understanding.)

There are many ways to talk about and advocate for the Energy Transition, and I believe that some of them are better than others. There are a lot of ways to be worse: trivializing the problem, muddying the waters, declaring premature victory, polarizing the issue along political lines, creating exhaustion with over-dramatized doom-and-gloom, and finally (just in general) saying things that are not true. Here I will take some of these tropes, metaphors, and rhetorical techniques out back behind the woodshed. Being nice to anyone at all is not within the scope of this section.

Breezy and sunny optimism

The transition is a hard problem, and we’re not served well by arguments that it is easy, or pretty much solved already.

The dot on the world map

Did you know that all of the world’s energy needs could be met with just solar panels covering 1.2% of the Sahara Desert? Versions of this argument with different power-source locations and assumptions abound on the Internet. Or you may see graphical maps like this one:

I think that this may have been an interesting argument when there might have been real questions about whether there is enough solar power to go around, but it’s time to retire it. The core challenges of wind and solar are intermittency and transmission, and we should reject any advocacy that starts off by assuming that those challenges don’t exist.

Plummeting module costs

The possibility of an affordable energy transition only exists because of the astonishing cost and efficiency improvements in core components like solar panels. As we discussed, though, the cheaper the core components get the less it matters that they are getting cheaper. Our best guides to what it’s going to cost going forward is the all-in costs of energy from actual deployments. In the case of utility-scale energy in particular, let’s talk about PPA prices rather than panel prices.

Triumphalism through cherry-picking

Earlier we discussed how you can make renewable energy look really promising by focusing on just one locale and timeframe, and by cooking up metrics that are designed to have positive-looking outputs. While these can help provide existence-proof examples of wind and solar winning, and those examples may be inspiring for further development, this inspiration comes at the cost of distortion of the overall picture.

Rooftop solar is the answer to all our problems

I have almost entirely ignored rooftop solar in the discussion so far, and focused on utility-scale renewables deployments, which is not because rooftop solar is unimportant. Small-scale solar (installations of 1MW or less) made up about 29% of U.S solar power in 2022. Residential rooftop solar is a substantial portion of this, at about 18% of U.S. solar power. Rooftop solar is a great thing, and we should encourage it.

Can rooftop solar be the entire solution? There are two overall answers:

1) There probably aren’t quite enough rooftops, and

2) It’s not obvious that rooftops are preferable to large-scale farms anyway.

As a thought experiment, total-world rooftop solar is the polar opposite of the “dot on the world map” (the single area in the Sahara Desert that could power the world). It is intrinsically distributed, has low transmission needs (to the extent that the rooftop powers the building below it). It is also intrinsically piecemeal, with individual roof owners needing to agree to each small-scale deployment, and lacks the economies of scale of utility-scale solar.

Estimates vary about the capacity you would get if you covered all of the world’s rooftops with solar panels. The most optimistic projection I’ve seen is that current world energy needs could be met by covering 50% of the rooftops, if you choose the rooftops carefully, meaning choosing the 50% that are in the sunniest countries and locations (which once again wishes away the challenge of transmission). This level of coverage would be an immense logistical challenge, and assumes the cooperation of every owner in the 50% you have chosen. Also, the area of available rooftops is currently fixed, is unlikely to grow exponentially, and the carbon cost of new construction is unlikely to make creating new rooftops a net win.

The future of solar energy will ultimately be some mix of large-scale and small-scale deployments (including rooftops), with that mix determined by relative demand and profitability, and there’s no strong reason to think that focusing unilaterally one of side of that will lead to better results. Finally, in the U.S. at least, the residential solar industry is in trouble.

The role of social norms and shaming (private jets)

I don’t fly on private jets. In fact, I am proud to say that I have never flown on a private jet. Why haven’t I? Because I can’t afford it. Would I fly private if I could afford it? Hmm, let’s cross that bridge when we come to it.

I am not a fan of the idea that we can reduce carbon emissions by scolding individual people who are responsible for a lot of carbon emissions. This trades a small net effect for a possibly-larger impact of persuading people that renewables advocates are scolds and killjoys. Large changes in carbon emissions will result from policy changes by businesses and governments. Private jet travel emissions in particular will be reduced primarily when and if such travel becomes either illegal, expensive, or carbon-neutral.

Scolding high-profile private-jet billionaires is, to my mind, an example of bundling two unrelated issues: 1) that private-jet travel is bad, and 2) societal questions about fairness and inequality of wealth. If you are angry at billionaires who fly private, which of those two issues are you angry about?

Aviation accounts for about 2.5% of greenhouse gas emissions, and private jet travel is about 0.9% of aviation. If the goal is to find good symbolic scapegoats, then private jet travel is a perfect target, but it seemingly accounts for only about 0.023% of our emissions problem.

Polarizing attachments

Idealists who want our climate policies and behaviors to change often want other kinds of change as well. There is a natural tendency to want to “bundle” the different kinds of desired change together into one package. Rather than advocating for cause A and cause B, they move to advocating for cause A&B. Why not? It turns a win and a win into a win-win!

There are two problems with this bundling strategy when cause A is climate change.

- Addressing climate change is a viciously hard problem, all on its own. Solving that problem itself is by definition easier than solving that problem plus another problem that it is bundled with. Why make an extremely hard goal even harder?

- Since climate change is a global problem that affects us all, it would be great if we could take it on with little reference to partisan disagreements. The moment that you couple it to another issue on which there is a partisan divide you are potentially turning it into a partisan issue itself. In our current (U.S.) polarized political climate that can add up to making it impossible to get any positive legislative progress on the issue. The politics of Covid vaccination is instructive here.

Here are some examples of polarizing attachments that should be renounced and avoided.

The Green New Deal

In the words of the Sierra Club, “[The] Green New Deal is a big, bold transformation of the economy to tackle the twin crises of inequality and climate change. It would mobilize vast public resources to help us transition from an economy built on exploitation and fossil fuels to one driven by dignified work and clean energy.”

This resonates for those who proudly trace their political lineage back to Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his “New Deal” that created social-safety-net programs like Social Security and Medicare. It instantly alienates everyone who politically traces back to Ronald Reagan, and who oppose large federal budgets and “government handouts”. In just three words of branding you manage to label the energy transition as a leftist program and lose the support of half of Congress for your climate legislation.

Climate Justice

“Climate justice connects the climate crisis to the social, racial and environmental issues in which it is deeply entangled. It recognizes the disproportionate impacts of climate change on low-income and BIPOC communities around the world, the people and places least responsible for the problem”, says the Center for Climate Justice at the University of California.

The poor, the marginalized, people of color, and the Global South are surely hit harder by climate impacts than is true for those insulated by greater privilege. The question is whether we gain any leverage on either climate change or social inequality by linking them together as a single problem. As with the Green New Deal, the linkage polarizes the issue and brands climate concerns as leftist concerns.

Labor unions and trade policy

“Climate change is the number one issue facing humanity. And it’s the number one issue for me” (Joe Biden).

“When I think climate, I think jobs, union jobs” (also Joe Biden).

The Biden administration has been a strong supporter of the energy transition, as well as a strong supporter of linking the energy transition agenda to domestic manufacturing and union jobs. As with the other polarizations, this turns out to be negative branding for the transition among those who lack Joe’s enthusiasm for unions. More importantly, what happens when the clean-energy priority and the union labor priority point in different directions? What if the fastest way to decarbonize the U.S. electric grid is to buy solar panels from China? Repeatedly it seems that when union labor is at stake, climate change is no longer this administration’s number one issue.

Environmental activism

A sad irony: the environmental-activism movement as we know it from the 1970’s shares substantial responsibility for the worst environmental catastrophe we have ever encountered.

Scenery environmentalism

Although we owe huge debts to the environmental movement for our clean air and our clean water, there is an arm of that movement that focuses on preserving large areas of land from the (visual) evidence of human encroachment. Vast pristine vistas can be spoiled forever by the presence of wind turbines on a distant ridge. The biggest problem with this version of “Not in my back yard” is that scenery environmentalists can have very large back yards.

Inability to give up on permitting

The National Environmental Policy Act (1970) laid out requirements on federal agencies to investigate the environmental impact of their decisions. Although this technically only applies to federal agencies, at least 18 states have directly analogous laws on the books. Significant construction projects usually require both environmental site assessments and review of biodiversity and wildlife protection.

These permitting requirements have been a key tool for environmentalists to combat pollution and habitat destruction, and to take aim at new coal plants, strip mining, and fracking. In addition to requiring scrutiny of negative impacts, the process here is largely designed to slow projects down, as every objection to a new project must be responded to individually, and often multiple waves of such objections are allowed. The same requirements apply to new wind and solar projects and partially explain why it takes years between when a renewables project is proposed and when ground is broken.

There are promising legislative efforts underway to streamline and speed up permitting, which clean energy advocates support, but many environmental groups are still opposed due to fears that it will speed up fossil fuel projects and weaken environmental protections.

Environmental impact and species extinction

Large construction projects inevitably disrupt local wildlife and can accelerate extinction of some species due to habitat loss. These effects are real, and wind and solar projects bring specific challenges of their own, particularly when it comes to birds. Even when renewables projects eventually get the go-ahead despite such objections and concerns, replying individually to each concern is a major source of delay.

Tradeoff denial

The way the permitting process is constructed, each negative environmental impact must be addressed individually. Gerard Schur has argued that the environmental movement in general suffers from tradeoff denial, and has difficulty balancing alternative sources of harm.

Individual renewables projects adversely affect the habitats and survival of particular local species. According to the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), “climate change currently affects at least 10,967 species on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species“. Even if your sole focus is on preserving biodiversity and combating species extinction, you need a tradeoff calculation that balances local habitat disruption with global impact of decreased greenhouse gas emissions. Whether or not such calculations are ever made, they don’t play a role in the permitting process.

Anti-nuclear

We’ll never know the alternative history with all its might-have-beens, but still have to ask: where would we be now if environmentalists had never mounted their decades-long opposition to nuclear energy? How much of the energy mix would now be supplied by nuclear energy rather than by coal and natural gas? How much lower would atmospheric carbon be today in that scenario?

The fossil fuel industry has long been an opponent of its nuclear competitor, starting as early as the late 1950’s, and alongside the environmental movement the industry lobbied both deniably and publicly to oppose it. As recently as 2011, Greenpeace was making the case for replacement of nuclear power plants with fossil natural gas (though they have since backed off this stance).

With 20/20 hindsight this opposition to nuclear energy was a mistake. At least in its peacetime uses, carbon has turned out to be more dangerous than plutonium.

The Ground Game

So where does that leave us (the global us) with the climate crisis and the energy transition?

Our Options

Here are the broadest alternatives:

1. Give up

It’s easy to look at any particular aspirational target (global net zero by 2030, anyone?), compare that target to the rate of progress to date, conclude that the target won’t met, or even that it’s delusionally optimistic, and then ask “Why are we even pretending to do this? We are going to fail at this goal. Why not devote all these resources to other problems?”

The challenge here is that combating climate change is not a binary yes-or-no problem (will we achieve net zero by 2050?). It’s continuous – what will be the parts-per-million of CO2 in the atmosphere on that future date? Lower is better, higher is worse. It’s also not just continuous, it’s cumulative. If we achieve net zero by 2055, it still really matters how high the PPM will be on that date, which means it matters greatly how much we emit in 2050, 2045, 2040, 2035 … Simply giving up means resigning ourselves to a disastrous fate resulting from unchecked emissions, which might still be largely averted.

2. Keep doing what we’re doing, and hope for the best

There’s a particular constellation of industries, companies, policies, and practices that make up the current energy transition approach. It results in some gains and inroads for renewable energy, which are celebrated. In the U.S., these policies are largely about passive encouragement of renewable energy industries via tax breaks and subsidies, as seen in the Inflation Reduction Act. From individual consumers we see some efforts to consume more responsibly (recycling, buying fuel-efficient vehicles, rooftop-solar adoption) which work best when the responsible behavior is also aligned with personal financial goals.

The resulting progress is great, and should be modestly celebrated, but as we’ve seen that level of progress hasn’t even started to dent the relentless upward growth of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Any suggestion that this amount of progress will carry the day should be combated with real numbers.

3. Reduce energy consumption

I have written at length about the transition challenge as being a race between growth rates of renewables production and overall energy consumption. Why don’t we just reduce energy consumption, or at least reduce the rate of increase of energy consumption? And why not incentivize reduced emissions even more directly by carbon taxes, which will reduce the very behavior that causes the problems? (This paragraph is in fact the first time that the phrase “carbon tax” appears in this piece.)

This is probably just learned helplessness on my part, but having seen the results of global agreements like the Paris accords, as well as legislative attempts in the U.S. toward taxing carbon, I am not optimistic about the likelihoods that democratic governments will be able to greatly restrain the consumption demands of their populaces. Totalitarian governments have more latitude, at least in the short and medium term, but even such regimes are not insulated forever and in every way from the consumption desires of their people.

The art of the politically possible

One of the easiest ways to have an unproductive conversation about climate change policy, even between two advocates, is to have one side make proposals that acknowledge current political realities, and have the other side describe “what I would do if I were king”, without either side noticing the disconnect.

It’s quite possible that gas (aka petrol – fuel for personal automobiles) should really be $20 per gallon rather than approximately $5, to properly reflect the externalities and damage from corresponding emissions. If I were king of the U.S. then $20/gallon gasoline would definitely be the law of the realm. What would happen if a U.S. Presidential candidate ran on a platform of $20/gallon gas? They would lose. What if they were elected on a different platform, and then worked with Congress to make $20 gas the law of the land anyway? They would be turfed out in the next election, and gas prices would return to $5/gallon. [Note 11/11/24: This post was written before the 2024 U.S. Presidential election.] The changes that can actually be made are limited by popular sentiment and political reality. A similar argument applies to efforts to levy serious carbon taxes, with its impacts on the kitchen-table issues of gas prices and home heating and air conditioning.

Where is the communitarian spirit?

Climate change is both a global emergency and a national emergency in the U.S. Those familiar with 20th century U.S. history are sometimes tempted to make analogies to WWII, and point to the sacrifices made by domestic citizens during that war effort, which included not just rationing of sugar, tires, meat, coffee, butter, canned goods and shoes but also rationing of gasoline. Why is such restriction of consumption seemingly unthinkable today? Admittedly, climate change is slow-moving compared to advancing armies, and CO2 is an invisible enemy that is difficult to think about and difficult to personalize. These differences, though, don’t feel like a complete explanation of why 2024 is so different from 1944 in terms of willingness to suffer privation to further common goals.

It’s possible that as the impacts of climate change become more severe and difficult to dismiss, the issue will rise in public consciousness to the point where we will see broad acceptance of the need for carbon taxes and rationing programs, but that day still seems to be far off.

4. Geoengineering

Clean energy is not the only conceivable route to keeping the planet cool – there are more direct engineering attacks on atmospheric carbon and on global temperature itself, which are collectively known as geoengineering. I won’t spend a lot of time on this vast subject, largely because (as I argue below) the likelihood that geoengineering approaches will make the renewable energy transition unnecessary is very slim.

Blocking the sun

Solar radiation warms the earth. The core of the greenhouse gas problem is that the atmosphere is transparent to most wavelengths of incoming solar radiation, but gases like CO2 and methane block the infrared wavelengths of radiated heat as it travels back up from the warmed ground and oceans, meaning that more of the heat from the sun is retained. Greenhouse gases act like a blanket that traps warmth, and higher concentrations of greenhouse gases make for a thicker and warmer blanket.

If the problem starts with solar warmth, why not just block or reflect more sunlight before it warms the ground and the oceans? We do have evidence from natural experiments that such cooling effects are possible, as there have been periods of cooler climate immediately following large volcanic eruptions which release sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere, which in turn causes more sunlight to be reflected back into space.

Although there are several styles of proposal for solar radiation management (SRM), including spraying seawater into the atmosphere and putting mirrors or reflectors into space, the leading candidate seems to be stratospheric sulfur injection (SSI), which mimics the cooling mechanism from volcanic eruptions. The scale of sulfur dioxide injection needed is immense, but not inconceivable. Extrapolations from volcanic eruption impacts indicate that 40 to 50 million tons of sulfur dioxide injected might be enough to temporarily reduce global temperatures by one degree Celsius.

Risks and drawbacks

Direct action like sulfur injection is scary, because the actual effects are hard to predict in detail. Isn’t it irresponsible to directly experiment with the Earth’s climate by injecting huge amounts of a man-made substance into the atmosphere, with unknown and unpredictable effects? I intentionally phrased this question, snarkily, so that it fits the aerosol injection proposals just as well as it fits our hundred-years-long irresponsible experiment with greenhouse-gas emissions. There is an argument that the warranty on the climate has already been voided, that we have already been geoengineering ourselves into unknown territory for decades, and that by the Pottery Barn rule it’s reasonable to take ownership of that geoengineering to get outcomes that we prefer, risky as that may seem.

Other risks and problems make aerosol injection less attractive than it seems at first. A lot of the issues are brilliantly detailed in science-fictional form in Kim Stanley Robinson’s “The Ministry for the Future“, including the fact that global weather patterns would be changed in uneven ways, leading to some countries being happy with the results and others seeing them as a disaster. What if weather changes cause the monsoons in India to stop, and widespread famine results? Who gets to make the calls about what outcomes are acceptable?

Another huge drawback is that sulfur injection is an intrinsically temporary solution – the sulfur falls out of the stratosphere within about three years, and so to maintain a given level of temperature reduction you need to keep replenishing it every year. If you stop, then temperature accelerates upward, quickly, to where it would have been if you had never started.

Carbon capture

Instead of building clean energy systems to avoid injecting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, we could in principle extract those gases from the atmosphere, and sequester or bury the carbon we extract. (This is known as Carbon Dioxide Removal, or CDR.) Trees are one way to do this, assuming that we can keep the trees intact or bury them so that their carbon isn’t immediately released back into the atmosphere again. One exciting new entrant in the carbon capture field is the idea of growing algae in ponds and then drying and burying it – this is claimed to be a much faster way to capture CO2 than trees are capable of.

To what extent can we make the energy transition unnecessary by capturing back atmospheric CO2, or capturing CO2 at the point of emission?

Rather than go through the poster-child carbon-capture technologies one by one, I will defer here to a long report on CDR by a climate and energy technology group (RMI), which assesses investment promise and timelines for 32 different CDR technologies. It should be noted that this organization is dedicated to combating climate change through technology, and is likely to be a booster of CDR rather than a detractor. Here’s the money slide (slide 26):

This calculation evaluates all 32 technical approaches, assumes that each one will pan out to maximal effect, and then plots out the resulting timeline of assistance level from CDR between now and the year 2100. This optimistic upper bound has the reduction rate from CDR in 2100 being roughly equivalent to current global carbon emissions. Note that the projection offers comparatively small assistance between now and 2050. So the most optimistic case is that CDR can help somewhat in the medium term (before 2050) and could address roughly all of our current emissions levels (not future levels) but not until 75 years from now.

Complacency tradeoffs

There was a period of several years where it was nearly taboo in the climate change community to mention geoengineering approaches – the idea was that the public might be distracted by the idea of a purely technological fix, become complacent, and lose all enthusiasm for an energy transition or reducing consumption.

In some sense we may be facing the opposite problem now, due to the modest but real successes of the energy transition to date, and the corresponding triumphalist happy-talk that I called out in earlier sections. Distracted by local and cherry-picked successes, we may trick ourselves into thinking that the energy transition as it has been unfolding will be good enough to avert the worst climate change outcomes, and so there is no need to pursue geoengineering. What seems most likely is that our situation is dire enough that we’ll need a “Yes, and” approach, and pursue all avenues in parallel, including geoengineering along with the energy transition.

5. Trust in future advances

Any attempt to talk about our future climate, including the exercise of setting emissions targets, relies on growth-rate projections of multiple complex phenomena at once: economies, industries, energy demand, renewable energy, and all the technical and scientific developments that feed into those things.

Exponential growth

Won’t we be saved by the exponential growth of renewable energy? Through much of this piece we have already assumed exponential growth – a growth rate of X% per year means an exponent of 1 + X%, and this is the way we usually talk about growth of populations, energy demand, and renewable energy. A exponential renewables growth rate of 0.1% per year won’t save us, where a sustained growth rate of 25% per year almost certainly would. Also a renewable-energy growth rate of 8.1% per year won’t save us if energy consumption grows by 8.0% per year.

Unknown unknowns

The progress of technical and engineering deployments is easy to predict in the short term and and insanely difficult in the long term. We know roughly what the utility-scale energy deployment landscape will look like one year from now, because any projects that matter have already been designed, planned, financed, permitted, and construction has nearly finished. A five-year horizon yields more uncertainty, but many of the projects that will deliver more than five years from now have already started. Thirty-year predictions of technology and science, on the other hand, have a risibly bad track record.

What conceivable scientific and technical developments could arrive that would suddenly change our outlook on energy and climate problems? The most obvious would be a cheap and limitless energy source, like cold fusion in a box. Another would be a carbon capture machine that scoops and sequesters carbon from the atmosphere, quickly, at scale, and with low power needs. Even unanticipated orders-of-magnitude improvements in energy storage or transmission (room-temperature superconductors?) could change the game.

Don’t rely on the deus ex machina

Although the history of 30-year predictions tells us that we can’t rule out breakthroughs like those above, we can’t rely on them either. For one thing, the difficulties of 30-year-timeframe predictions cut both ways – we have allegedly been close to cheap fusion power for more than 50 years now. We can imagine and we can hope, but just as competent financial advisors will decline to factor your future lottery winnings into your retirement planning, we need to cover the bad scenarios along with the good ones.

The second reason for non-reliance is that anthropogenic climate change is no longer a long-term threat – it’s a short- and medium-term threat – and mass deployment of even breakthrough technologies can take serious time. Say that someone invents and prototypes a cold fusion box tomorrow that costs $1000 to make (after factory scale-up) and that pumps out 100kW of free electricity (or 876 MWh per year) forever. This would be about 1/100th of the cost of a 100kW solar kit, and with no intermittency. To approximately equal the world’s current solar energy production, we would need to build and scale up factories, and then manufacture about 1.5M of these boxes, and then deploy and integrate all the boxes appropriately – whether that is to all the individual homes, businesses, and factories that use the electricity, and/or to all the current utilities that distribute electric power to the grid. Even if the magic technology arrives tomorrow, how many years will it take to deploy to match even the level of current solar generation, let alone to catch up with solar’s exponential growth?

Time is tight enough that we may have to go to climate war with the technology we have, not the technology we hope to have. Or to put it positively, the miraculous technologies we asked for decades ago may have already arrived, and they are the modern solar panel and the modern wind turbine. Now we face a mere matter of deployment.

6. Accelerate the transition

Having dispensed with the other alternatives, what is left is the energy transition.